A little late, but here it is at last. I read so many excellent books last year that it would have been hard to choose six or so, though I did post my favourites on Facebook as advent books throughout December. Here, though, I'm going for just one. What follows is the piece I wrote for WRITERS REVIEW in the autumn.

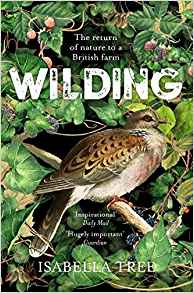

What a fascinating book this is! It covers so much, overturning several preconceptions along the way, that I hardly know where to start. So I'll begin at the end,

where Isabella Tree comments on the benefits of natural surroundings for mental health, and the sad fact that many people nowadays have little exposure - through choice or circumstance - to wild

nature. Readers of this blog probably know that Robert Macfarlane and Jackie Morris were spurred to work together on The Lost Words - a beautiful book which

won Jackie Morris a well-deserved Kate Greenaway Medal for illustration - by news that the Oxford Junior Dictionary was ditching such words as acorn, bluebell,

wren and otter to make space for terms deemed more relevant to today's world: celebrity, blog, broadband and suchlike. Macfarlane

and Morris's widely-acclaimed collaboration is a timely and important book, and so in its different way is Wilding.

Isabella Tree and her husband Charlie Burrell, inheriting his family estate of 3,500 acres, at first continued the arable and dairy farming already

established there, but found that their hard-baked clay soil did not produce good yields. Could there be a way of letting their land fulfill its potential - not for commerce, but for wildlife?

Inspired by a Dutch project on land earmarked for industry but then abandoned, they learned how the presence of grazing animals - greylag geese, then large herbivores - had produced surprising

results; close grazing kept the water fringes clear and tree growth in check, providing habitat for a wealth of insects, birds and small mammals. It's often assumed that any fertile land, if left

untended, will become mature woodland; but, as Isabella Tree points out, this notion overlooks the presence of grazing herbivores such as the ancient aurochs, tarpan and bison which preceded

human intervention, later replaced by deer, domesticated cattle and pigs. Perhaps, she thinks, we have the wrong idea about ancient forests. She quotes Oliver Rackham: "To the medievals, a Forest

was a place of deer, not of trees. If a Forest happened to be wooded it formed part of the wood-pasture tradition."

Wondering if this minimal-intervention approach would work with their own land, Isabella and Charlie sought grants from English Nature (now Natural England), the

government's advisory body. Unlike most applicants for funding they had no clear plan for what was in effect an experiment: their plan was, over twenty-five years, to see what would happen if

they fenced their land to make it deer-proof, a major expense, and introduced Longhorn cattle, fallow and later red deer, and Exmoor ponies. As in the Dutch project, they chose tough, sturdy

animals that could fend and forage for themselves and withstand all weathers.

Of course the Knepp project couldn't fully replicate natural ecosystems without including apex predators - lynxes or wolves - to keep the numbers of cattle, ponies and deer in check.The Dutch project, leaving weak and elderly animals to die from illness or starvation, had met with justifiable opposition; at Knepp, with the land crossed by footpaths, such a hands-off approach couldn't be justified on humane, aesthetic or even practical grounds. So the grazing animals are culled, and their meat sold. Apparently grass-fed beef is delicious, and pasture grazing is certainly the most environmentally efficient way of producing meat, although it's a luxury few can afford.

The Knepp experiment, now sixteen years on, has produced inspiring results. Iconic species such as turtle dove, nightingale and purple emperor butterfly have moved in; beavers have been introduced, their dams creating marshy wetland which supports wading birds, amphibians and bog plants. The softening of water edges is so important for flood defences, another re-think: rather than funnelling water into hard-edged channels, it can effectively be dispersed and soaked up, to the benefit of pasture and wildlife. Another keystone creature is the humble earthworm, whose importance has been underestimated to the detriment of soil health.

Few individuals will be able to replicate the Knepp experiment - Tree and Burrell owned a substantial swathe of land and were able to recruit expert help and

funding. But I hope their findings will influence government and NGO policy on land management and conservation. Among many revelations, perhaps the most significant is that if we intervene less,

nature can be trusted to restore itself. Whether there's time, in the face of climate breakdown, to attempt this on a wider scale, is impossible to know - we may be too far into our reckless

uncontrolled global experiment with the world's climate and ecosystems.

I'd say that Wilding is essential, even exciting, reading for anyone interested in nature, wildlife, ecosystems and climate change -

and I think most readers will find surprises and revelations to make them see the countryside, and our role in it, with fresh eyes. And I don't want to end without giving a flavour of the

writing: although packed with information, comparisons and statistics, Wilding also has moments of lyrical joy, such as this description of a nightingale's song: "It

throws the ear with unexpectedness ... florid trills, first rich and liquid, then mockingly guttural and discordant; now a sweet insistence of long, lugubrious piping; then bubbling chuckles and

indrawn whistles; and then, suddenly, nothing - a suspended, teasing hiatus before the cascades and crescendos break forth again ... these pulsating strains issuing from tiny vocal chords belting

out like organ pipes, throwing the music of the tropics into the English night air."